In Georgia midterms, health care takes a back seat to the economy

Georgia Democrats are trying to motivate voters on health care after a spate of hospital closures, GOP policies limiting Medicaid, abortion restrictions and rising medical costs. But even reliable Democratic voters with pressing medical needs are still grappling with economic worries, raising questions about how far health care issues can go in turning out the base or in driving independents and nonvoters toward Democrats.

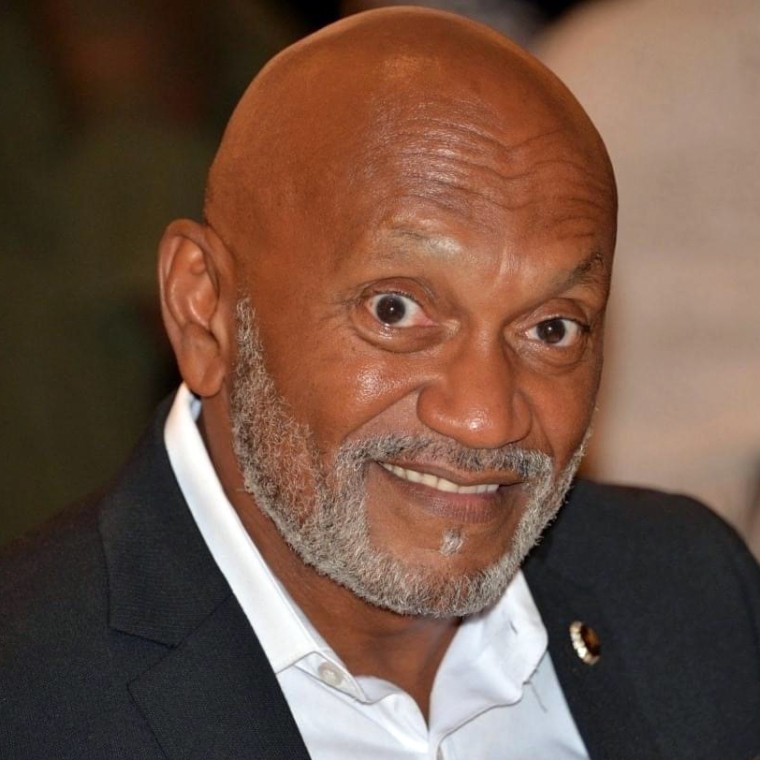

Shortly before Atlanta Medical Center in the downtown-adjacent Old Fourth Ward neighborhood closed for good last week, June Barlow Callaway learned that a CT scan performed there had detected cancer in her throat. Callaway had worked for the 460-bed hospital’s food-service contractor for 22 years, but after getting her diagnosis in October, she concluded it was time to “sit down.”

“Being 73, nobody is going to hire me,” Callaway says. “My body just won’t take this push and pulling no more.”

Within weeks, she started chemotherapy — at Grady Memorial, now one of two remaining hospitals in downtown Atlanta — stocked her pantry with items from a local food bank and filed for unemployment.

Callaway is among the more than 2 million Georgians who have voted early. She chose Democrats down the ballot, as she has most of her life, in part because Sen. Raphael Warnock and gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams have campaigned on lowering health care costs, she says. But even for her, health considerations aren’t necessarily top of mind.

Atlanta’s 11.7{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} inflation rate in August was second only to Phoenix’s, the latest available data show, and far above the current 8.2{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} national average. Callaway’s bills for her Medicare-covered cancer treatments don’t compare with her $856 mortgage payments, or the electricity bill that swelled to around $300 from $200 in recent years, or the cable package she ditched this summer.

Callaway, who doesn’t have children, recently moved a cousin into her four-bedroom home to help her cover expenses. She’s considering taking on a second roommate but worries about living with someone she doesn’t know.

“I might have to resort to that, but I hope not,” she says. “We’re cutting back on everything.”

While voters may be tightening their budgets for many reasons, the prominence of economic pressures is making it harder for Democratic candidates across the country to galvanize supporters over other issues.

In an October Quinnipiac poll of likely Georgia voters, 43{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} ranked inflation as their top issue, with abortion (14{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f}), election laws (11{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f}) and gun violence (10{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f}) trailing far behind. The results were even starker along party lines: 73{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} of state Republicans ranked inflation number one — with no other issue cracking double digits — while 27{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} of Democrats put abortion first and just 12{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} prioritized health care. (The poll’s margin of error was +/- 2.9 percentage points.)

The Warnock and Abrams campaigns are racing to move the needle. Both have highlighted policies that limit health care access in Georgia, such as its new six-week abortion ban and a decision by Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, who is running for re-election, to decline additional federal funds to expand Medicaid, the program that provides health coverage to low-income Americans.

In an ad last month, Abrams drove 85 miles from Atlanta Medical Center to Macon, home of the nearest Level 1 trauma center should Grady Memorial fill up — a distance she said risked the lives of Atlantans needing emergency care. Rather than accept some $15 billion in congressional pandemic aid that would have benefited Medicaid patients, Abrams said, Kemp “has squandered that money by refusing to bring it to Georgia.”

The Kemp campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment. The governor’s partial Medicaid expansion — targeting some 50,000 people — recently cleared a legal hurdle after the Biden administration objected to its work and job-training requirements. Kemp, who has campaigned mainly on the economy, also used federal Covid aid for cash payments to low-income residents, distributing more than $1 billion to more than 3 million people.

Georgians have witnessed health services dwindle before and during the pandemic, straining the state’s medical system even as regional health care costs rise.

In September, according to the latest data available from the Labor Department, medical services cost nearly 6{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} more across the South than a year ago. Nearly half of Georgia’s 159 counties have no OB-GYN, according to the Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce. And while roughly a third of rural hospitals in the U.S. are at risk of shutdown, Georgia has experienced more closures of rural critical-access hospitals over the past decade than any other state, according to researchers at the University of North Carolina.

That trend has recently hit Georgia’s capital. Atlanta Medical Center, run by the private nonprofit Wellstar Health System, was one of only two Level 1 trauma centers in a city that has added more than 65,000 residents in the past year alone. At least 15 primary and specialty care offices associated with AMC are closing their Atlanta locations as well.

Wellstar said in a statement that it has spent years investing “significantly in capital improvements like medical equipment and building renovations” despite prolonged operating losses that became untenable. “AMC has long cared for the most vulnerable patients in our city without the public financial support provided to local safety net hospitals, and without this critical additional funding, we just could not sustain operations.”

State Democrats have sought to tie the shutdowns to limited Medicaid access, with Warnock pointing to his record in Congress where he “capped the cost of insulin and prescription drugs for Georgia seniors, fought to expand Medicaid and worked to lower health care costs,” his campaign said in a statement.

Georgia’s 13.7{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} uninsured rate was the third highest in the country in 2019, according to U.S. census data, and the rate for rural residents is expected to surpass 25{bf0515afdcaddba073662ceb89fbb62b6b1bf123143c0e06b788e1946e8c353f} by 2026. In 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that nearly 500,000 uninsured adult Georgians would have been eligible for Medicaid had the state expanded the program.

Warnock’s GOP opponent, Herschel Walker, has criticized Medicaid and says he wants people “to get off the government health care.” The Walker campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Wellstar has said that treating more Medicaid patients would have helped forestall its Atlanta closures but not stopped them. Even so, it isn’t clear the issue is firing up voters.

“Medicaid expansion is not connected to your day-to-day living in Georgia,” said Fred Hicks, a political strategist who worked on Warnock’s 2020 campaign. “It’s too amorphous for people, and Democrats have just done a really bad job of messaging on that.”

Other political experts say Medicaid concerns could fuel Democratic turnout, even marginally, in combination with other issues. “It might get some people to go and vote who hadn’t planned to vote,” says Charles Bullock, a political science professor at the University of Georgia. In a highly polarized purple state, “fairly small movements on different issues could prove decisive,” he said.

Like Abrams, some Atlanta community leaders are betting that the hospital closures will resonate, especially in the heavily Democratic metro Atlanta area. Michael Stinson, pastor of East Point First Mallalieu United Methodist Church, says he and other church leaders have discussed the shutdowns in sermons. And they’re planning a senior health seminar on Nov. 5, days before polls close.

“I’m sure the fact that there’s no hospitals South of I-20 is going to be part of that conversation,” he said, referring to a major east-west corridor in central Atlanta.

A former physician himself, Stinson, 64, recently learned that the doctor who manages his asthma and high blood pressure is leaving the Wellstar family medicine office he visits, wary of being swamped by patients spilling over from closed-down sites.

That includes AMC South in East Point — home to Stinson’s church and 15 minutes outside Atlanta proper — which Wellstar shuttered several months before ceasing operations at AMC downtown. East Point is composed largely of Black and brown residents. Just six months after opening an urgent care clinic in place of AMC South, Wellstar last week announced its closure, too.

Some see the shutdowns as exacerbating racial disparities in health care access in Atlanta, where a 2018 Trulia analysis found 25.3 health care providers per 10,000 residents in the city’s majority-white census tracts, compared with 9.8 in majority-Black tracts.

“Depending on where you live in Atlanta, you could live to be 60 or you could live to be 80,” says Atlanta city council member Liliana Bakhtiari, an independent whose district includes parts of Old Fourth Ward. “[Wellstar] bought five hospitals. Two of them were in low-income, majority-minority areas that needed a lot more help. And they closed those two down and kept three in North Fulton open, where it’s more affluent and predominantly white.”

Wellstar rejected this characterization, saying it “made substantial investments in each facility, including AMC and AMC South,” with nearly $350 million in improvements to the former. “Wellstar has always and will continue to serve low-income and minority communities across the region. We are the largest provider of uncompensated care in Georgia, providing more than $915 million in charity care last year,” it said.

For now, June Callaway is driving to her oncology appointments at Grady, about 7 miles from AMC South, which she used to walk to. The trips require her to pay for gas and parking. And while she’s grateful Medicare covers most of her bills, she’s still listening for a solution that none of the major candidates, Democrat or Republican, seem to have readily at hand. “I’m looking at somebody that is going to be for the community,” she says, “that’s going to help us with the health care — bring it closer to us.”